By Nayanika Samanta

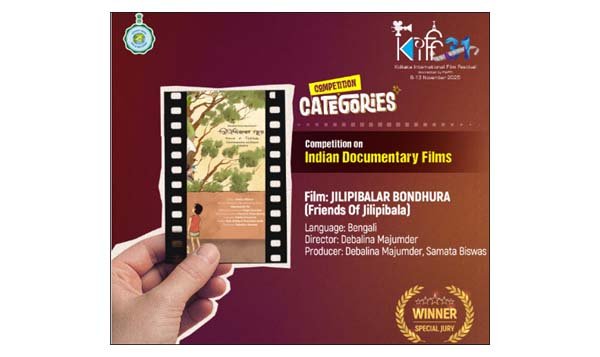

Kolkata, Nov 23 (UNI) Jilipibalar Bondhura, a meditative documentary that captures the fragile relationship between a child and the fast-eroding natural world around her, stands out as a testament to Kolkata’s lost ecology.

The film, which received a Special Mention at the recent Kolkata International Film Festival (KIFF), tenderly chronicles the world of toddler Simran – affectionately monikered Jilipibala – and her enchanted interactions with the thriving ecosystem surrounding a towering peepal tree in South Kolkata.

Through Simran’s eyes, the film observes the vibrant birds, insects, blossoms and small creatures that populate this urban ecosystem, a world that slowly begins to shrink as the tree and its neighbouring green cover come under threat from relentless construction and urban upheaval.

The director Debalina Mazumdar recalls, “Simran lived in our house as a tenant between 2018 and early 2020 and she grew up watching that tree. I would point out the flowers and the birds to her. I filmed small portions, without any intention of turning them into a documentary.”

But last year, things changed drastically. The peepal tree, though lying just beyond the sanctioned construction zone, was nonetheless in grave danger.

“It was this urgency that became the seed of the film,” she explains.

“That small cosmos of birds, butterflies and insects, those were her first friends,” she reflects. “This is precisely why the film bears the name Jilipibalar Bondhura. She grew up alongside them.”

When a java apple and later an old mango tree were felled last year, young Simran’s distress was captured on camera, footage that eventually became pivotal to shaping the documentary’s environmental argument.

“Children see things adults tend to overlook,” Mazumdar told UNI. “She would point out a flower or a bird as though it were a tiny marvel. That innocence, I realised, became the film’s essence.”

“Environmental ruin is not a saga restricted to remote woodlands,” she says quietly. “It’s creeping into our own neighbours.

“If the film stirs even a slight bit of consciousness among the viewers, that will be enough for us”.

The 30-minute documentary is woven from almost twelve years’ worth of archival footage, interlaced with material captured as recently as January. The edit took close to six months, with Debalina and producer Samata Biswas combing through an enormous volume of material.

Biswas, who co-produced the documentary, admits that putting a “budget number” on the film is nearly impossible. “How can you put a price on twelve years of shooting?” she asks. “We’ve only paid for the essentials, the edit, the soundscape, the colour, the festival submissions. Debalina hasn’t been paid for directing or filming. This project is, quite simply, a labour of love.”

Since its KIFF premiere, the film has generated keen interest from cinema societies, film clubs and educational institutions eager to screen it for wider audiences. The team intends to send it to more festivals across India, including Kerala and other independent circuits.

Majumder is currently developing two parallel projects, one exploring the environmental issues titled “Sobujer Smriti” (Memories of the Green) and the other one, an episodic film based on Partition, capturing the everyday lives of Muslim communities across India.